Design Thinking

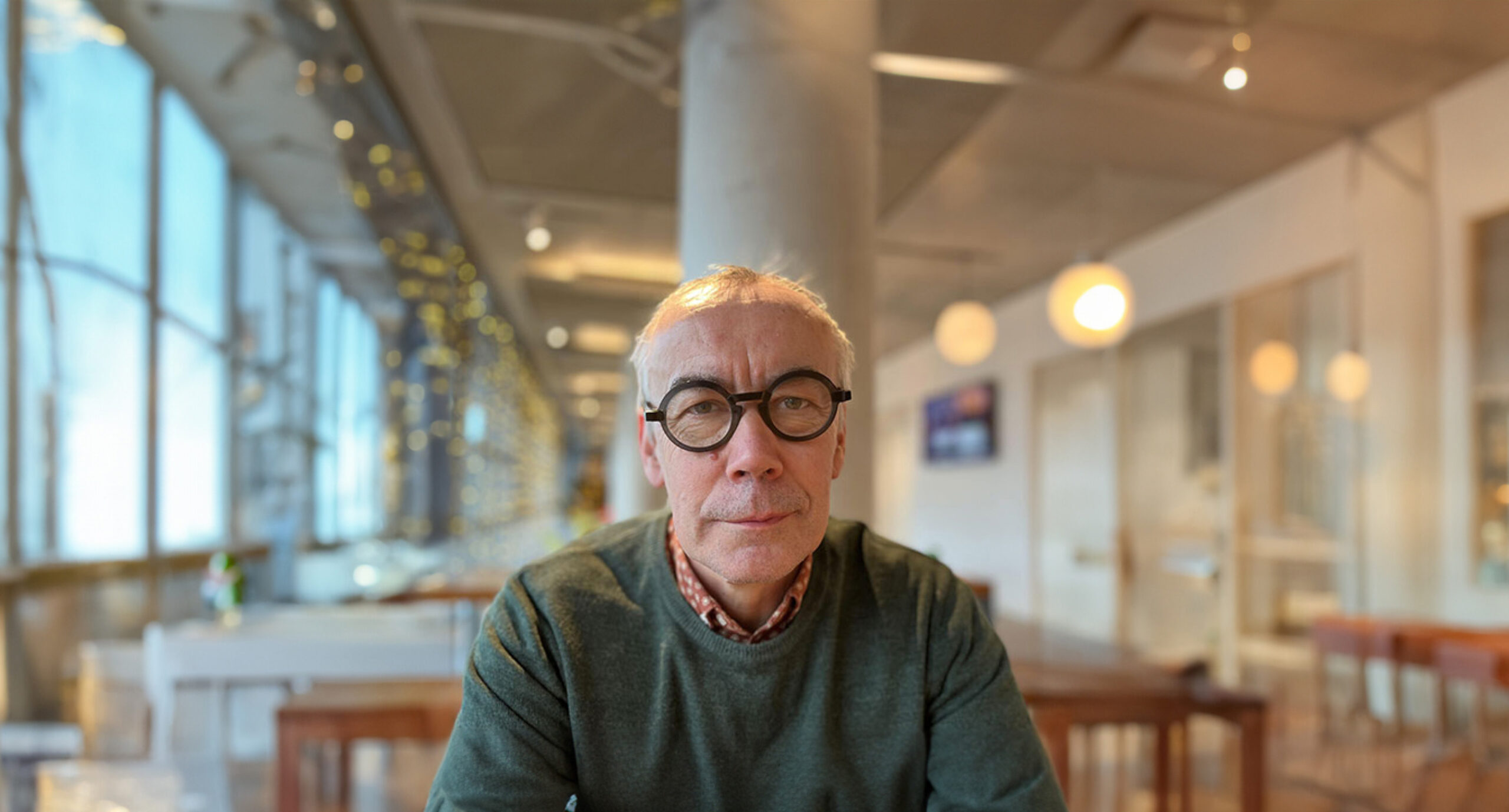

Interview | David Rudlin, Director of Urban Design at BDP

From successful city centre development to the dark side of an unregulated housing market, renowned urbanist David Rudlin discusses the current urban climate, and how high quality, high density design can build better cities for the future.

When it comes to building better cities, what is the role of the urban designer?

The first thing to say is that our job is completely different to that of architects. Urban designers don’t design buildings, we create a three-dimensional envelope for buildings to fit into and, in doing so, we shape the size and proportion of the public realm. It’s a very different process.

If you think about Paris, much of the city was designed by Haussmann. He didn’t create any buildings, but he set the parameters around where the streets go, how wide they are, the height of the buildings on each side of the street, and so on. The three-dimensional space that he created is still being followed by designers in Paris, and it’s what makes Paris the city it is.

As an urban designer, what would be your number one priority to improve our cities for the future?

It would be to establish a strong enough regulatory framework to make sure what we urban designers envisaged actually gets built. As well as designing the three-dimensional space, we write the design code, which is a set of instructions to each of the multiple architects who will be delivering buildings within the overall master plan. This design code is our instruction to them, outlining what they need to deliver on their plot.

Elsewhere in the world, this relationship is well understood. Whether it be New York, or Paris, or wherever, the master plan is very clear and every architect knows what they can do within it, and they generally follow the rules. In Britain, we have a very different system in which architects and developers always feel they can question the design code.

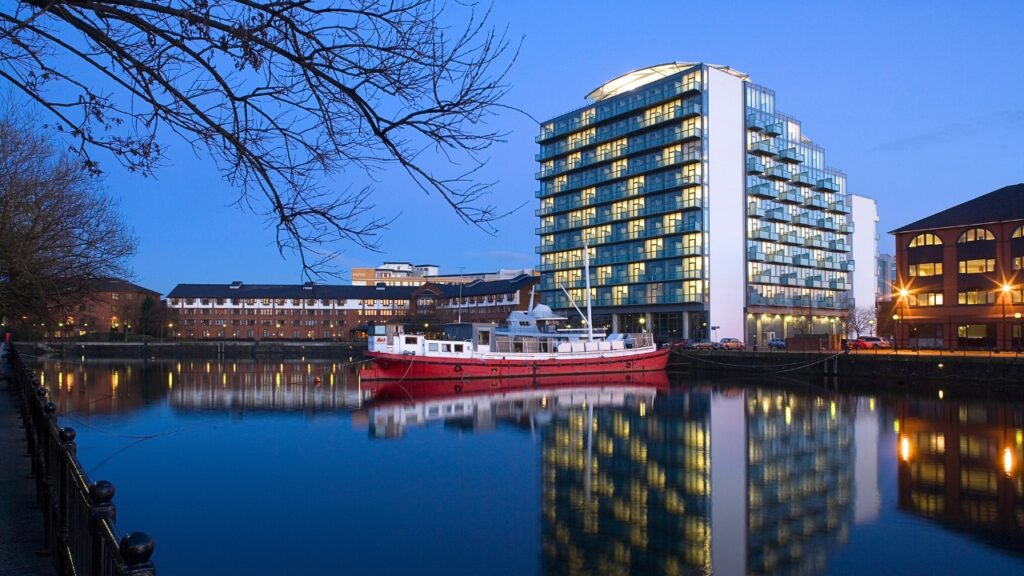

You can see the results of this in Bristol, for example, where the Bristol & West building on Temple Quay South is built across the main axis of the original plan. The plan was created with a vista going down to the river, then Bristol & West came along, and it was such an important occupier the plan was sacrificed. This happens all the time in the UK.

That must be frustrating, as it's so permanent.

That’s it. Once it’s done, the plan is gone. That’s the other thing about urban designers, we work remotely. So we’ll be commissioned to complete a master plan, but most of the buildings will be delivered when we’re no longer appointed – sometimes 20 years afterwards – so having that long reach, and the ability to control what’s done in the future, is really hard.

But doing good quality urban design and knowing how spaces work is really important. Underlying that is the whole idea of urbanism and creating spaces that work for the people who use them. I’m quite happy for architects to push the boundaries – that’s all for the good because it increases creativity – but don’t ignore them. If you’re going to bend the rules, at least be able to justify why.

High density living has a bad reputation. What do you think needs to change to move away from these stereotypes?

The word density is a real issue. Any ‘density’ sounds too high, so maybe we need a different word for it. When it comes to the bad reputation of high density housing, we talk about cramped little flats, and no open space, and so on. But in New York, around Central Park is incredibly high density, with massive condominium apartments. There’s also a huge amount of open space to go with it. You can design high density living well, and you can design it badly. I think that’s the problem.

Are you seeing new housing models emerge in response to changing needs - like co-housing, for example?

I think there’s certainly an element of that. Taking development in Manchester, there are developers creating four-bedroom flats in which all bedrooms are the same size with en-suite bathrooms. These are designed specifically for non-related adults house sharing. It’s moving away from assuming that single person households require one bed flats or studios, and instead creating another way of living, in a larger flat with other people, which is what a lot of people are now having to do in our cities.

Another big area is Build to Rent. Ownership rates have dropped hugely over the last 20 years. The first round of city centre apartments, back in the 2000s, were built for sale. The flats were bought up by private landlords, often off plan, and then rented out. Some blocks would have 30+ different landlords and nothing was coordinated.

The new Build to Rent blocks are different in that they are all funded by pension funds like Legal & General, and managed properly by a single landlord. The ground floor is given over to communal facilities – shared kitchens, TV rooms, gyms and yoga studios, all sorts of things – and above are flats that range from one-bedroom options, to those that cover two floors and rent for £3000 a week. You can have pets, and you can decorate – you can make it your home. It’s a very different approach.

Good quality urban design and knowing how spaces work is really important. Underlying that is the whole idea of urbanism, and creating spaces that work for the people who use them.

David Rudlin

So it's an attractive lifestyle, and the communal areas help build communities within high density living?

Yes. At that top end of the market this model is an interesting new way of looking at how housing is provided. But at the bottom end of the same market, there’s exploitative practices going on. With ‘co-living’, occupants have access to a shared laundry and kitchen, but the flats can be tiny. A few cities around the UK are now saying they aren’t going to allow co-living anymore because it can be exploitative.

Where does quality assurance come in? Does there need to be better regulation to prevent this kind of exploitation?

It can be done through planning. The best guide is the London Housing Design Guide – a city-wide initiative from Sadiq Khan – which contains, among other things, minimum space standards for flats. Lots of authorities have adopted this London code to apply to new housing in their area.

Permitted development rights are a whole other issue. In 2013, the government changed the planning laws so that, basically, office blocks could be converted into flats without any planning permission. In my opinion, it was a very stupid idea. There are flats in London now that have been built without any windows, if you can believe it? Talk about giving high density a bad reputation. They have changed the legislation now to include minimum space requirements but still, there’s a lot of office blocks in London which have been converted into really poor-quality flats.

On the flip side to that, are there examples of great high density development in the UK?

Yes, there’s lots. I was in Hackney Wick in London the other day, around the Fish Island area, where there’s really good quality mid-rise, high density housing. Manchester is another example. There’s a real demand for housing in Manchester – around 10,000 new households arriving in the city every year – and this creates a dynamic environment in which the city needs to grow. This allows much more to be done in terms of experimenting with different forms and housing models.

There are around 40 towers in Manchester of more than 30 storeys – it’s turned into a mini-Chicago. But within the city you’ve also got places like Ancoats which, because it’s a conservation area, doesn’t have any towers but is still a great example of really good high density housing, with a new square carved out in the middle which is full of activity and goings on.

Bristol, likewise, has always had a high demand for housing, but it’s unusual in the UK in that it’s a big city that has never been particularly run down. All the other large cities in the UK have been through a period of intense decline which has left lots of gaps, lots of run down areas, and now they’re regenerating. Bristol never went through that so it’s a different background to development in the city.

You delivered the master plan for Temple Quay North. What is your experience of development in Bristol?

It’s an interesting conversation in Bristol. I feel it’s not that people don’t want high density housing, it’s that a lot of development has been stopped by the planners. Whether you present a good scheme or a bad scheme, it seems to receive the same number of objections, and I honestly don’t think the quality of what’s been built in Bristol reflects that level of attention.

I keep going back to Manchester, where they have a more laissez-faire attitude to planning, and the quality of what’s been built is not as bad. Better than in Leeds, for example, which is another difficult city to get planning permission. In my experience, when you’re faced with so many objections you often end up with mealy-mouthed buildings that, in an effort not to offend anyone, are actually really dull. In Manchester, the buildings are so much more confident and brazen, and they are the better for it.

What would be your five core principles for successful urban design?

The first is that it should be street based – with walkable, lively streets, rather than windswept plazas. Mixed use would be the next one. It can’t just be housing, it needs to work in terms of employment, and amenities, and so on. I don’t have an issue with height provided the buildings are well designed and relate to the street. Neighbourhoods need to be well-planned in terms of having height in the right place, and having density in the right place. You don’t want to be putting high-rise housing in the suburbs and low-rise in the city centre. You need to understand where you’re sitting within the urban hierarchy, and that the density is appropriate to that level.

We talked about decent quality flats with good internal space, so I’d add internal space standards. Another big issue we have at the moment is double loaded apartments. Most apartments are designed with a corridor that has a flat on either side, which only looks out in one direction. When you build that at high densities, you end up with some flats with only north facing windows. One of the things we’ve been exploring is how to achieve dual aspect apartments that have light coming from two sides. That is really important in high densities, otherwise you end up in shade all the time, which can’t be good for anyone.

Quality of design and internal arrangement become much more important when designing high density. All space matters, and how those spaces work is vital to success.

David will be speaking on Thursday 28 March at our Future Cities public talk, presented in partnership with BDP. He will be joined by Jo Davis, UK Chair of Avison Young, and Alex Hearn, Director of Economy of Place at Bristol City Council, to discuss the changing face of our cities anyhow we can design for equity at high density.

Design Thinking is a series of thought-provoking interviews in which leading practitioners share their personal insight and opinion on key issues affecting the design of our world.

You Might Also Like